5 Reasons Black Women Have Still Not Achieved Equality in 2020

Women’s Equality Day on August 26 marked the 100 anniversary of the 19 Amendment, granting women the right to vote. I was planning to write a long post explaining the many ways in which women are still not equal to men in the United States. But the killing of yet another Black man shot seven times in the back by a Wisconsin police officer changed my mind.

The gravity of the ongoing injustice faced by Black Americans every day made me want to get right to the most important point about the status of women in America. The biggest failure of Women’s Equality Day is that Black women, Indigenous women, and other Women of Color have largely been ignored, overlooked, and left behind in the struggle for equality.

There is no question that civil rights laws have led to substantial progress for women in the workplace. In what some think of as a “post-gender” society, young girls are taught they can do anything, be anything, and achieve anything they can imagine. Yet the reality is that a glass ceiling still places barriers to women — especially Women of Color — in the boardroom and positions of leadership.

Civil rights laws have also failed miserably to protect women who provide essential services in low-wage jobs. As we have learned from the pandemic, those jobs are primarily held by BIWOC, who suffer disproportionately from the effects of living in poverty with inadequate access to housing, health care, childcare, and other essential support services.

The fact is that Black women and other Women of Color fall at the bottom of nearly every scale of economic security. How did we get to this place? The same way we got to the disproportionate number of Black men who are killed by the police every year in this country. The legacy of slavery and systemic racism are baked into every institution and into the hearts and souls of every American. We have not done the hard work to confront this legacy and heal the unconscious bias that permeates our society.

The Fractured History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement

When the fight for women’s suffrage began in the 1860’s, many feminists were also abolitionists. But the movement splintered over passage of the 15th amendment, which granted suffrage for African Americans. Some influential suffragist leaders argued fiercely against Black men getting the vote before white women. Their stance led to a break with abolitionist allies, like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and Frances E.W. Harper.

Even after the movement splintered, Black women worked tirelessly for women’s suffrage and finally prevailed with passage of the 19 Amendment in 1920. Yet most Black women did not enjoy the right to vote for another 45 years. Jim Crow laws in the South prevented Black women and men from voting by imposing poll taxes, literacy tests, and voter I.D. requirements. The Voting Rights Act (VRA) signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965 was meant to overcome the barriers that prevented many Black people from exercising their right to vote.

As we know from the current political landscape, Black women have been the backbone of the Democratic party for decades. Yet they continue to face barriers to exercising their right to vote. In 2013, the Supreme Court rolled back fundamental safeguards of the VRA, setting off a rise in voter suppression including voter purges, discriminatory voter photo ID requirements, restrictions on early voting, and a reduction in the number and hours of polling places. Most recently, the U.S. Postmaster General has instituted changes to the postal system that many believe are intentionally designed to suppress the mail-in vote during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Make no mistake, these efforts are not accidental. They are targeted to disenfranchising communities of color, just like the Jim Crow laws of an earlier era. One hundred years after passage of the 19 Amendment, Black women continue to struggle to exercise their fundamental right to vote.

Equal Treatment Does Not Lead to Equal Results for Black Women

More than five decades have passed since the passage of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 promised equal treatment in employment irrespective of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 also promised women equal pay for equal work. Yet in 2020 women — especially women of color — lag behind men in nearly every measure of economic security.

Why does this continue to be the case? To understand why women of color can’t seem to catch up, you have to understand the philosophy of formal equality. Civil rights law were intended to prohibit intentional discrimination and to provide equal opportunity. With the limited exception of short-lived affirmative action programs, they cannot help to compensate for past injustices and discrimination.

It is no surprise that laws that assume people start out on equal footing have failed to provide equal results for Black women, who have endured centuries of slavery, patriarchy, and structural racism.

The Gender Pay Gap Reveals Stark Differences Between White Women and Women of Color

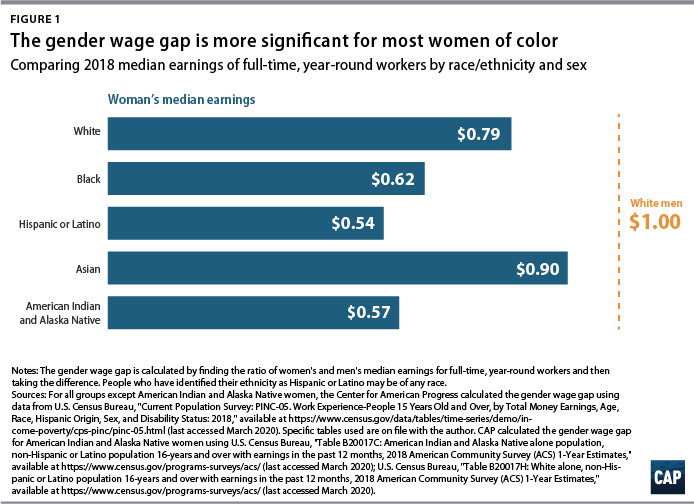

One way to measure women’s inequality is the Gender Pay Gap – the difference in earnings between women and men. Women in the U.S. consistently earn less than men, and the gap is considerably wider for most women of color.

According to Census Bureau data from 2018, white women earned, on average, just 79 cents for every $1 earned by men of all races. For BIWOC, the gap was significantly higher. Black women earned an average of 62 cents per dollar, Indigenous women earned 57 cents per dollar; and Latinas earned just 54 cents per dollar. (See Figure 1)

Women’s Equal Pay Day marks the day in the year which it takes for women to earn what men did for the previous year. In 2020, that day was March 31 for all women collectively, and not until August 13 for Black women, who had to work nearly 8 months longer than men to earn the same amount.

What accounts for this great disparity? There are five key reasons that laws based on a formal equality model cannot lead to equal results for Black women and other Women of Color in the workforce.

1. Unconscious Bias and Institutional Racism

Most civil rights laws require a plaintiff to prove that the reason she did not get a desired job or promotion was based on the employer’s intentional discrimination. In the absence of a smoking gun, intent is exceedingly difficult to prove.

Moreover, if we have learned anything from the history of race in this country, it is that most discrimination is unconscious and built into the structure of our organizations. It is not only white supremacists who make discriminatory employment decisions; it is liberal white bosses who believe they don’t see color and don’t have a racist bone in their bodies.

That unconscious bias explains why, even in well-paid professions like law and higher education, women of color are woefully under-represented in leadership and high-status positions. Somehow there are never enough qualified applicants. If a woman of color does manage to get hired, she doesn’t get invited to the right meetings, doesn’t get the high-profile assignments, and her voice is not heard at meetings. Then she is seen as less qualified when it comes time for promotion. Formal equality does nothing to address this hidden, unconscious institutional bias.

2. Intersectionality

Black women and other women of color are discriminated against based on multiple aspects of their social identities. They face the same patriarchal attitudes as white women, and the same racist stereotypes as Black men. Yet the law does not have a way to understand and analyze these complicated intersecting identities.

Professor Kimberle Crenshaw, who coined the term “intersectionality,” uses the metaphor of an accident at a traffic intersection to describe this issue. In a 2016 TEDWomen talk, she explains that if you are standing in the path of multiple forms of exclusion like race and gender, you’re likely to get hit by both. The harm women of color face at these intersections is more than the sum of its parts, but difficult for the law to quantify and address.

3. Gender Roles and Family Responsibilities

Although society is slowly changing and men are taking on more childcare responsibility, a study by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2018 confirmed that women still take on the majority of the caregiving, housework, and other unpaid family responsibilities. Women on the “Mommy track” often fall behind in their careers, lose opportunities for advancement, or even drop out of the workforce during their prime parenting years.

Women also face discrimination in the workplace based on pregnancy. The Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) requires employers to treat pregnant women as well as other employees but does not require them to accommodate special medical needs arising out of pregnancy.

Pregnant women still face challenges on the job, especially if they work in jobs that require heavy lifting or moving. Low-paying retail, warehouse, and factory jobs are often held by women of color, many of whom are their family’s sole or primary breadwinner and cannot afford to lose their paychecks. Formal equality requires too many working women to choose between their job duties and the health of their pregnancy.

4. Job Stratification and the Feminization of Poverty

Societal and structural racism and sexism often influence the jobs that women work in. Women, especially women of color, are more likely to be clustered in low-paid jobs that do not provide the wages, hours, or benefits that people need to achieve economic security and stability.

Women make up nearly two-thirds of the workforce in the lowest-paying jobs, which include service workers in the food, restaurant, retail, and caregiving sectors. As the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us, these workers are essential to our every day lives, yet they face severe economic hardship.

BIWOC of all races and women born outside the U.S. are over-represented in these low-paid jobs. For example, Black women make up only 6.3% of the overall workforce but represent 9.7% of low-wage workers. More than one in four women in the low-paid workforce have at least one child under 18 at home. The vast majority – especially Black mothers — are the sole or primary breadwinners for their families. Nearly two-thirds of these struggling mothers lived at or near the poverty line in 2018.

Raising the federal minimum wage could lift low-wage mothers out of poverty, but nothing in the formal equality model requires employers to treat low-wage workers equally to workers in higher-paid occupations.

5. Pervasive Sexual Harassment

Title VII prohibits sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination, but we know from the #MeToo movement that far too many women have suffered pervasive harassment at work. From politics to the entertainment industry to sports, we have watched as once-powerful men have been brought to justice through the efforts of women banding together on social media to say “no more.”

Although the hashtag #MeToo was popularized by white women exposing exploitation by powerful white men like entertainment mogul Harvey Weinstein, it had its origins in the advocacy of African-American sexual assault survivor and activist Tarana Burke, who first introduced the phrase in 2006 to raise awareness specifically for marginalized victims.

Black women have been fighting against sexual violence and sexual exploitation since before the Civil War, when slaves were routinely subjected to sexualized beatings, sexual harassment, and sexual assault. Fast forward to modern times, it is no surprise that Black women and girls continue to be the target of white male power and exploitation. This comes at a tremendous cost not only to their careers, but also to their mental health. It can lead to anxiety, depression, and traumatic stress disorders that impact the rest of a woman’s life if left untreated. Yet BIWOC have been largely left out of the conversation about workplace sexual harassment.

Conclusion: The Way Forward to a More Inclusive Society

As we have seen, civil rights laws and formal equality are necessary to address intentional discrimination in the workplace, but they are not enough to overcome centuries of structural racism and sexism. That will require a cultural sea change and the dismantling of centuries of white privilege and unconscious bias.

With the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many other Black and Brown people, this country is facing a racial reckoning. It is time for the women’s equality movement to do the same.

We can start by centering the voices of Black women and other women of color in conversations about law, policy, and social change. White women need to step back and listen to BIWOC, and then take action on what they say is needed to achieve meaningful equality.

On the legal front, we need to look beyond formal equality to a model based on fairness and equity. This framework has not been embraced in U.S. law, but we have a good model in international human rights law.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against All Women (CEDAW), known as the women’s bill of rights, was adopted by the United Nations in 1979. The United States is one of only five member nations in the world that has not ratified CEDAW.

Like U.S. civil rights laws, CEDAW was passed to end discrimination and sexual violence against women and girls. But unlike U.S. law, CEDAW has an implementation body that works with member states to affirmatively design laws, policies, programs, and services that will lead to quantifiable gains for women in the workplace and other arenas. This is an equity model that focuses on fair results rather than fair procedures.

If an equity framework were adopted in the U.S., it might lead to passage of legislation such as universal health and childcare, paid family and medical leave, paid sick days, and higher minimum wages. These supports would put Black women and other Women of Color on a more equal footing so that they could benefit from the economic rewards of their participation in the workforce.

The struggle for racial and gender equality has been fought on the backs of Black and Brown women for too long. With the nomination of our first Black woman Vice-Presidential candidate and the racial reckoning that is taking place across the country, it is time to demand that the United States at last live up to the full promise of Women’s Equality Day.

This is well said! I would love to meet with you and discuss actions that the YWCA can put in place to move towards women equality!!

Thank you for your kind words. I look forward to meeting.